Oni

- For other articles under the name "Oni", see Oni (disambiguation).

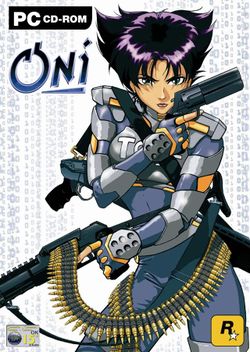

Oni is an action video game developed by Bungie West, a satellite studio of Bungie, and released in the U.S. on January 29, 2001[1][2] for Windows, Macintosh, and PlayStation 2. See Credits for a complete list of the names behind Oni as well as links to interviews with key members of the Oni team.

Inspiration

Work on Oni began in 1997 when Bungie decided to found a second studio, Bungie West, with the initial employees being Brent Pease and Michael Evans. The concept for Bungie West's first project was devised by Pease, whose primary influence was the animé film Ghost in the Shell.[3] It took one year of conversation with Alex Seropian before the project was greenlit.[4] Pease and Evans had been programmers at Apple working on game-related technology, so their first step was to begin programming Oni's engine while gradually hiring employees to produce concept art and game content. "Oni" was meant to be a development code name that referenced the game's inspiration – Pease considered oni's meaning to be "ghost".[4][note 1][note 2] The characters Konoko and Commander Griffin of the Technology Crimes Task Force are analogous to Motoko Kusanagi and Chief Aramaki of Section 9 in Ghost in the Shell. Early development presented Konoko as a cyborg, furthering her resemblance to Motoko.

Oni's concept artist Alex Okita cited Bubblegum Crisis, Akira and Trigun as influences in addition to Ghost in the Shell.[5][6] He particularly cited Kenichi Sonoda, character designer of Bubblegum Crisis, as an influence on his work.[7] Later, Lorraine McLees also showed her familiarity with Sonoda and Ghost in the Shell creator Masamune Shirow in a sketch showing Konoko in three different styles. In August of 1999, Hardy LeBel was brought in as Design Lead and revamped the story.[8] He cited Neon Genesis Evangelion as a personal influence when doing so.[9][10] The final version of Oni abandoned the cyborg nature of the heroine and introduced original concepts such as the Daodan Chrysalis and SLDs.

Further reading: Early story, Positioning statement, Concept art.

Hype

The earliest online hype came from the existing Bungie community.[note 3] As the Oni project gained popularity, a dedicated online community emerged in the form of Oni Central and the Oni Central Forum.

Bungie West initially promised various ambitious features such as human-like AI, sophisticated melee combat, realistic level architecture, complex particle dynamics, battles with a large mech (the "Iron Demon") and multiplayer capability. Two trailers were made for Oni, one in 1998 and one in 1999, reflecting the visions for the game during its time in development. These trailers and various screenshots were analyzed eagerly for evidence of Oni's ground-breaking features.

After E3 1999, Oni received the Game Critics Award for "Best Action/Adventure Game".[11] This award is given to games exhibited at that year's E3, which are usually still in development and expected to release soon.

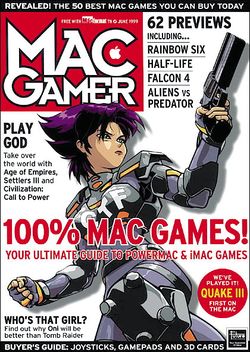

After an initial onslaught of advertising which saw Konoko appear on many gaming magazine covers, Oni's development stalled (as discussed below), and Bungie suspended the advertising of the game so as not to expend their marketing budget before Oni was even released.[12] At the same time, Bungie's HQ in Chicago had their own game under development; previously known only by its code name "Blam!", in 1999 it came to be known as "Halo" and slowly drew attention away from the oft-delayed Oni as images and trailers for it began to appear.

Further reading: Trailers, History of the Oni community, Oni Central interview with Bungie West, Adrenaline Vault interview with Doug Zartman.

Troubles

Oni was originally expected to be released in the fourth quarter of 1999,[12] but as that time approached, the release date was pushed back. This occurred repeatedly, until finally the rumored release date was as late as March 2001.[note 4] Some of the uncertainty came from Bungie's typical reluctance to announce or adhere to fixed release dates.

However, unbeknownst to the public, development of Oni was troubled from the start. The team was young and inexperienced, and development suffered from a lack of direction. A great deal of code had been written and assets created without producing a story that was playable from start to finish. Transferring data from the professional software used for level modeling and animation into Oni wasn't even possible until the very end of 1997.[note 5] By mid-1999 it became clear to management back in Chicago that the game was not going to be ready by year-end, so Hardy LeBel was added to the team with the goal of bringing focus to the development efforts and producing a shippable product.

At the same time, turnover at the Bungie West office began with the departure of the AI programmer in the summer of 1999 (a replacement would not be hired until January 2000[13]). The end of 1999 saw the departure of one of the level designers and then Brent Pease himself (with his Project Lead title being passed to Michael Evans).

LeBel, Evans and the team began honing the gameplay, shaping the final story, and figuring out what features or content would have to be dropped in order to ship the game before it was too late; Bungie was secretly suffering from serious money problems (see § Buyout below). In May of 2000, it was announced that multiplayer was being removed from the game due to latency issues and lack of time to create suitable arena levels for network play.

In June of 2000, it was announced that Bungie had been acquired by Microsoft. This caused an upset among Bungie's fan base, which mostly consisted of Mac users. They considered Microsoft to be Apple's nemesis, and now the company behind the upcoming Xbox console had taken the most popular game developer from the Mac world and would be incorporating them into their office complex. The effect of the acquisition on Oni's development was dire: it meant that Bungie West needed to finish their work as soon as possible and join the rest of Bungie in Redmond, Washington.

In order to ship the game by year-end, the Bungie West staff worked massive overtime for several months straight.[note 6] During this "crunch" period, the unexpected departure of the graphics programmer led to his replacement and a minor overhaul of the graphics code.[14] Technical and/or gameplay issues required all 14 levels to have their geometry significantly altered over the course of 7 months.[9][15][note 7] According to Hardy LeBel, "It was as bad a crunch as there has ever been in the video games industry."[16] It is only due to this final push that a playable and enjoyable game was forged out of their years of prior work.

Completion

Oni went through a short period of beta testing, starting just before September 2000,[17] during which leaked beta builds of the game surfaced on the Internet.[18][19] As Bungie West reached the end of development, Oni's publisher, Take-Two Interactive, granted them an extra month to polish the game, even though it would mean missing the holiday season. This final period of asset development apparently spanned October 2000, during which time the training level was added.[20]

The Windows version was gold mastered in November 2000 after fixing some final bugs in the engine,[21] and the Mac version was finalized in December after Mac-specific bugs were resolved.[22] The PlayStation 2 version did not reach gold status until January 22, 2001, one week before the release date that had been announced in November 2000, indicating additional difficulties with the port's engine code.[23] The Windows demo, released in mid-December,[24] contained Chapter 1 and Chapter 4. A later demo was released with Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 instead. The Mac demo, released a few days after the original Windows demo,[22] only ever contained Chapters 1 and 4.

As Oni finally neared completion, Bungie resumed their advertising, now partnered with Take-Two, who were in the process of taking over the Oni IP as Bungie prepared to join Microsoft (see § Buyout below). Promotional artwork was produced by Lorraine McLees as well as artists commissioned by Take-Two, and a four-issue comic book was produced under Take-Two's supervision and published by Dark Horse. Take-Two's PR efforts, however, seem to have been focused mainly on the PlayStation 2 version of the game.

Further reading: Leaked Mac beta, Dark Horse's Oni comic, Promotional art.

Release

Oni was finally released, much later than originally expected, on January 29, 2001 in the United States.[25] The game retailed in the U.S. for $39.95 on Macintosh and Windows and $49.95 on PlayStation 2,[26] and was rated "T" for Teen by the ESRB.[1]

Oni was translated into other languages: Russian, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Chinese and Japanese.[27] These localizations included re-dubbed dialogue except for the Chinese localization which only translated the in-game text. The localizations were critical to building Oni's fan base, much of which is outside of primarily-English-speaking countries. Additional distributions of the game such as Brazilian Portuguese and Slovak only translated the manual and did not change any of the data on the game disc. The European-language releases for Mac and PlayStation 2 were delayed until March 2001. The Japanese releases for Windows and Mac didn't come out until the fall of 2001.

Oni's storyline is fairly straightforward, although it has been called "understated". Because the story takes place over about a week and a half in the game's timeline, there is little room to develop the characters or setting, although large amounts of additional information are to be found in consoles scattered throughout the levels.

The developers achieved a unique blend of gunplay and hand-to-hand combat, with fluid controls and a camera that ensures that the action is always visible. Gunplay is fairly standard for the action genre, with some added emphasis on realism (Konoko only carries one weapon at a time, and a gun's ammo is tracked persistently whether it is being handled by the player or an enemy). The melee component of the game is particularly complex, employing over 2000 animations, and is frequently the main element that fans point to when praising the uniqueness of the gameplay.

Oni uses an in-house graphics engine developed for this game; it was optimized for handling levels with larger indoor environments than typical games of the time. The levels were designed by actual architects, giving them a more realistic look than many contemporary game worlds. The texturing in the game is minimalist, a style chosen to try to match the look of animé.

Further reading: Gameplay, Plot summary, Console text.

Reception

The overall consensus of the critical reviews was that the game was good, but not great; Oni has a metascore of 73/100 from critics, but an 8.4/10 from the website's voters.

Professional critics tended to dislike the ambitious melee element, complaining of counter-intuitive or unresponsive controls (if they found the game too hard), or the easily accessible basic combos (if they found the game too easy). Some reviewers were unimpressed by environmental graphics that were not as rich as other games of the time (the simple look of Oni was partly due to the attempt to mimic animé backgrounds, and partly a result of the game mostly taking place in offices and other real-world structures).

Upon Oni's release, many felt cheated because the game did not deliver on all of its promises (a not-uncommon issue in game development). The most notable shortcoming was the absence of LAN multiplayer, which had been featured in playable demos at expo booths in 1999 and 2000.

Some previously hyped features were missing, such as the AI characters being able to dodge gunfire and work together. This was attributed to the turnover in the AI engineering position after the original programmer was not able to complete all the tasks in the timeframe that she stated she would.[28] (However some hidden AI abilities have been found in Oni's engine, either disabled, unfinished, or not utilized by the game's mission scripts.)

Some of the game's content was cut as well. This included an entire planned level (BGI HQ) and the highly anticipated Iron Demon, the large mech shown in-game in the 1999 trailer. Gaps in the numbering of the game files led fans to believe that at least five chapters were cut before release, but this was mainly due to content that was moved around or consolidated into fewer levels.[28]

Further reading: Pre-beta content, Pre-beta features, Reviews, Multiplayer.

Buyout

"In November 1999, we acquired 19.9% of the outstanding capital stock of Bungie Software Products Corporation for $5 million, of which $4 million was paid and $1 million is payable in May 2000. Bungie is a leading developer of software games for the PC platform."

"In June 2000, the Company sold its 19.9% equity interest in Bungie Software (“Bungie”) to Microsoft Corporation for approximately $5,000[,000] in cash. The Company did not realize any gain or loss on this transaction. Separately, the Company sold its exclusive Halo publishing and distribution rights to Bungie for $4,000[,000] in cash, a royalty free license to Bungie’s Halo technology in connection with the development of two original products and all right, title and interest to the Myth franchise and the PC and PlayStation(R) 2 game, Oni. The Company recorded this transaction as net sales of $5,500[,000] after giving effect to the receipt of $9,000[,000] in cash and $5,800[,000] of assets (consisting of $2,800[,000] relating to Oni, $1,500[,000] relating to Myth and $1,500[,000] relating to the license to use Halo game engine technology for two original products), net of $9,300[,000] of assets sold."

Bungie had seemed to enjoy great success as an independent publisher ever since they released Pathways into Darkness in 1993. However, Bungie was initially a Macintosh developer, and even their domination of the Mac's small game industry meant limited success in real financial terms[note 8] (though Bungie also began porting their games to Windows starting with Marathon 2). Bungie took advantage of their indie status to avoid the strict deadlines which are normally enforced by video game publishers, refusing to release their games until they were totally satisfied with them.

It is believed that Bungie began suffering from a shortage of cash around 1998 when the Myth II uninstaller bug was discovered and cost them at least $800,000 to correct.[29] This might have been difficult to absorb for a studio not accustomed to a disciplined release schedule. The next game to release after Myth II was to be Oni in 1999, but as Oni's release date began to slip further and further, it became clear that Bungie had underestimated the time required to finish the game by more than usual. In the meantime, Bungie was bankrolling two studios instead of one. Thus, the decision was made to partner with Take-Two Interactive; on August 13, 1999, it was announced that Take-Two would acquire 19.9% of Bungie in exchange for the publishing rights to Oni and Halo.[30] Take-Two also began work on a port of Oni for the upcoming PlayStation 2 console.

This deal didn't seem to change business much for Bungie, especially since another studio was performing the PlayStation 2 port. But considerably more shocking news was revealed on June 19, 2000, when Bungie announced its acquisition by Microsoft.[31] It turned out that Bungie's monetary woes had not been solved by Take-Two's influx of cash, and so Peter Tamte, Bungie's executive vice president, had been tasked with finding a buyer for the company. Take-Two acquired (among other things) all rights to the Oni and Myth IPs in exchange for its stake in Bungie and its publishing rights for Halo. Take-Two valued the Oni IP at $2.8 million, and the Myth IP at $1.5 million.[32][note 9]

The acquisition of Bungie by Microsoft also meant the dissolution of Bungie West as Bungie moved all their employees to a single office in Redmond, Washington. Some Oni developers stayed with Bungie and went on to contribute to the Halo series, such as LeBel, while some left to join or start other game studios.

Further reading: Rights.

Sequel

Clearly Take-Two expected big things from Oni (see their valuation of Oni above, as well as their promotional efforts under § Hype). They had assigned Rockstar Canada (now known as Rockstar Toronto) to start work on a PlayStation 2 port of Oni in 1999, and it was released alongside the Windows and Mac versions of Oni; however, the port is regarded as an inferior version of the game due to technical limitations and control issues.

At first, Take-Two seemed intent on investing in Oni as a franchise. Shortly after Oni's release, a simple game billed as an Oni prequel (developed by Quantum Sheep) was released for WAP-enabled cell phones.[33] More significantly, it was rumored[34] that Take-Two had put Oni 2 into production at Angel Studios; however, no sequel was ever officially announced. In 2016, an actual development build of the cancelled game was leaked.[35] Interviews with former employees of Angel Studios revealed that the game had been in development for about two years without a clear direction, and the troubled project was finally cancelled when the studio was acquired by Rockstar in 2002 and renamed Rockstar San Diego.

Further reading: Oni (PlayStation 2), Oni 2 (Angel Studios), Oni (WAP version).

Future

Take-Two has sold off some dormant franchises to outside developers, although Oni is not one of them. Upon the separation of Bungie from Microsoft in 2007, there was fervent speculation about Bungie returning to their older franchises. In an interview, Bungie's CEO at the time, Harold Ryan, was asked specifically about Oni:

- 4Players

- Since we're on the subject of strong franchises: is there perhaps a chance to bring back Oni?

- Harold Ryan

- (laughs) Oni isn't currently one of those projects we're looking at, but one should never say never.

We'd be happy to work with the individuals who made Oni.[36]

One thing is certain: the current Bungie staff has little in common with the group that produced Oni (there is only one Oni developer still working at Bungie – Chris Butcher – as of October 2023). There is probably little sentimental or monetary incentive for the studio to buy back the IP and produce a sequel.

When Oni was released, Bungie did not hold to their usual practice of releasing level-building tools for their games, since professional and costly software was used to produce Oni's levels.[note 10] There was a plan to release information on the game's file formats to aid modders in developing their own tools, and to also release the tool that Bungie West developed for importing data from the professional software they used,[4] but by the time of Oni's release, ownership had transferred to Take-Two, so Bungie no longer held the rights to the code and tools.[37] Thus, it was left to the fans to create modding tools after investigating the inner workings of the game on their own.

Since Oni's release, the fan community has been working on mods and writing gameplay and modding tools for the game. Gradually the modding abilities of the community have extended to nearly every aspect of the game. The game applications for Windows and macOS are also maintained and improved through patches. Various fan projects have taken on the subject of an "Oni 2" storyline.

Further reading: History of Oni modding, Anniversary Edition, Gameplay tools, Modding tools, Engine patches, Oni 2 (fanon).

References

Footnotes

<div style="

">

- ↑ However Hardy LeBel, the writer of the story, indicated here and here that he understood "oni" to mean "demon" and had written the final story with that in mind. The final story incorporates many elements of the mythical oni, as explored in Oni (myth) § Connections to the game.

- ↑ At one time during development, the name "Mnemonic Shadow" was considered according to the Marathon Story Page.

- ↑ Oni discussion on the Marathon Story Page. Bungie fans first started talking about the newly-announced Oni (and the E3 1998 trailer) back in May-June 1998, unaware that it would not release for another two and a half years.

- ↑ Discussions on Oni Central Forum of: a fall 1999 release date, a summer 2000 release date, a fall 2000 release date, and finally a spring 2001 release date. These "release dates" were generally rumors, ephemeral dates used by online stores for pre-orders, or vague estimates by Bungie PR, not official statements. Nevertheless, it was clear that Oni was taking longer than planned to finish, which was a cause of some concern among Bungie fans.

- ↑ "After almost a year all they had were some stick figures walking in a box; hardly a killer demo, much less a new frontier in gaming. […] Eventually, Brent had a 'eureka' - just before New Year's Eve 1998, he had a breakthrough. He was able to match the power of these professional tools with their new engine." Inside Mac Games, "Sneak Preview: Oni", 1999.

- ↑ Michael Evans said, "Most of us were working 14 hours a day 7 days a week" in this interview.

- ↑ Also see Hardy LeBel, "Learn Level Design Class 9 - Integrating Game Mechanics", Dec. 17, 2016, at 11'38", where he talks about a "month of weekends" spent adding the jello-fix boxes.

- ↑ Dean Takahashi's book "Opening the Xbox" claims on page 238 that a Bungie game never sold more than 200,000 units, but that number is based on a misunderstanding, because the Chicago Reader article below talks about an initial shipment of Myth II numbering 200,000 units, and also states that the first Myth game sold 300,000 copies total.

- ↑ The sale of Bungie to Microsoft has an interesting historical footnote: according to Ed Fries, who was VP of game publishing at Microsoft, Steve Jobs angrily called MS CEO Steve Ballmer immediately after the Bungie acquisition was announced; sources within Bungie have stated that Apple themselves had been close to offering to buy Bungie at the time. In order to appease Apple (a business partner of Microsoft) over the loss of a major Mac game developer, Microsoft helped form a new company which would publish a Mac port of Halo as well as other games. It was named Destineer, and headed up by none other than Peter Tamte of Bungie. Destineer would go on to publish a port of Halo for the Mac in 2003. (sources: [1], [2], [3], [4])

- ↑ 3D Studio MAX ($3,495) and the Character Studio plugin ($1,500) for character modeling and animation, AutoCAD ($3,750) for use by the architects in modeling the levels, and Lightscape ($500) for calculating the radiosity lighting solutions. (sources on tools used: [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]) (sources on prices of tools: [10], [11], [12], [13], [14])

Citations

<div style="

">

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Godgames.com, "Gathering of Developers Ships Oni Nationwide for the PC and Macintosh", Jan. 29, 2001. This is referring to the U.S. release; see § Release for info on other releases.

- ↑ GameSpot, "Oni Receives Final Approval", unknown date.

- ↑ Inside Mac Games, "Sneak Preview: Oni", 1999.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Bungie.org, "Interview with Brent Pease", 1999.

- ↑ Glixel, "Flashback: 'Oni', Bungie's Cult Classic Inspired by 'Ghost in the Shell'", Mar. 30, 2017.

- ↑ Bungie.org, "Interview with Alex Okita", 1999.

- ↑ OniCore, Interview with Alex Okita, 1999.

- ↑ Inside Mac Games, "Interview: Oni's Hardy LeBel", 2000.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Apple.com, "Conquering Demons: Bungie on Oni", Feb. 2001.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "Re: The Analytical reasons behind Oni's influences", Sep. 2, 2000.

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Game Critics Awards".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Oni Central Forum, "Re: Matt- could you address this?", Aug. 29, 2000.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "I'm pretty sure Chris Butcher has joined Oni", Jan. 23, 2000.

- ↑ eBay, "Bungie Oni for Macintosh - Autographed", May 17, 2021. Stefan tells the story in the Description section of the page.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "Re: Oni basic questionare", Jul. 6, 2002.

- ↑ mrixrt, "Bungie's Forgotten Franchise - Oni", Mar. 11, 2019, 16 minute mark.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "New news groups?", Aug. 28, 2000.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "Leakage?", Nov. 27, 2000.

- ↑ Usenet alt.games.tombraider thread, "ok wtf!", Nov. 5, 2000.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "Re: is the "new' movie really the old trailer", Oct. 30, 2000. Also, a gold master candidate produced on Oct. 30, 2000 already contained the training level. The timestamp on the Windows retail game data is Nov. 3, 2000, so all assets were done by that point.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "ONI gone GOLD", Nov. 20, 2000.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 See Oni Central Forum, "Re: It's coming... soon", Dec. 18, 2000, which showed that the Mac demo would not be ready until the Mac version of the game reached Gold Master status, and Oni Central Forum, "MAC DEMO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!", Dec. 22, 2000, celebrating the release of the demo. However, the official confirmation of Mac GM status didn't come until Jan. 3, 2001.

- ↑ Daily Radar, "Oni Gets SCEA's Approval ", Jan. 22, 2001.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "ONI DEMO!", Dec. 17, 2000.

- ↑ Oni Central News Archive, Jan. 2001.

- ↑ Bungie Store: Oni Bundle. The UK price seems to have been £30 per this review.

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "What language is your copy of Oni in?", Sep. 2011.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Oni Central Forum, "Re: More questions... (mainly for chef...)", Jul. 7, 2002.

- ↑ Chicago Reader, "Monsters in a Box", Mar. 23, 2000.

- ↑ SEC 10-K filing for Take-Two Interactive, Oct. 31, 1999.

- ↑ IGN, "Microsoft Buys Bungie, Take Two Buys Oni, PS2 Situation Unchanged", Jun. 19, 2000.

- ↑ SEC 10-K filing for Take-Two Interactive, Oct. 31, 2002.

- ↑ Fastest Game News Online, "Oni Prequel Announced", Feb. 6, 2001.

- ↑ Oni Central News, Apr. 1, 2001.

- ↑ Documented by the game preservation YouTube channel PtoPOnline here.

- ↑ 4players.de interviews Shane Kim and Harold Ryan, Oct. 5, 2007 (translated from original).

- ↑ Oni Central Forum, "Re: Ok Matt, you knew we'd ask...", Oct. 5, 2000.